The beginnings of the diocese

It is unlikely that any diocesan structure existed prior to Rathbreasail; rather, the local bishops would simply have been members of monastic communities in the area. While they would have had some prestige deriving from their office, it was the abbots who held power and were administrators of the church system. The Vikings were primarily responsible for the establishment of the diocesan system in Ireland. Indeed, the city of Limerick played a leading role in that development through the work of its first bishop, Gilbert. Initially, he was consecrated as bishop for the city and subsequently took charge of the diocese when it was formed in the year 1111. One of the most remarkable features of the diocese is that its boundaries have not changed significantly since that time. They were in turn based on an older territorial division, a Munster sub-kingdom ruled by the Ui Fidgente kings. On his death in 1145, Gilbert was succeeded by Bishop Patrick, who may have been of Viking ancestry, probably taking the name at his consecration. The next bishop, of whom we have record, is Brictius. He took part in the Synod of Cashel in 1172 and represented Limerick at the third Lateran council in 1179. It is of interest that he travelled to Rome with St. Laurence O’Toole, the first canonised Irish saint.

It is unlikely that any diocesan structure existed prior to Rathbreasail; rather, the local bishops would simply have been members of monastic communities in the area. While they would have had some prestige deriving from their office, it was the abbots who held power and were administrators of the church system. The Vikings were primarily responsible for the establishment of the diocesan system in Ireland. Indeed, the city of Limerick played a leading role in that development through the work of its first bishop, Gilbert. Initially, he was consecrated as bishop for the city and subsequently took charge of the diocese when it was formed in the year 1111. One of the most remarkable features of the diocese is that its boundaries have not changed significantly since that time. They were in turn based on an older territorial division, a Munster sub-kingdom ruled by the Ui Fidgente kings. On his death in 1145, Gilbert was succeeded by Bishop Patrick, who may have been of Viking ancestry, probably taking the name at his consecration. The next bishop, of whom we have record, is Brictius. He took part in the Synod of Cashel in 1172 and represented Limerick at the third Lateran council in 1179. It is of interest that he travelled to Rome with St. Laurence O’Toole, the first canonised Irish saint.

The Black Book of Limerick

The Black Book of Limerick, a manuscript of various medieval documents relating to the diocese, provides valuable information for that period. In 1201 an enquiry was held into the ecclesiastical property of the diocese. The jury who conducted this survey was made up equally of Irish, Norman and Viking members indicating the cosmopolitan nature of the diocese at that time. This invaluable list of early thirteenth century churches is printed and discussed in Begley’s History of the Diocese. In the taxation return for 1302 we learn for the first time that the diocese had been divided into deaneries and the proxy tax of 1418 gives another list of churches which affords a valuable comparison with the situation in 1201. It is to Cornelius O’Dea, bishop from 1400 to 1426, that we are indebted for the two great treasures of the diocese, the O’Dea mitre and crozier. He was also responsible for the compilation of the Black Book, which was returned to its rightful home in the diocese during the recent episcopate of the late Bishop Newman.

The Black Book of Limerick, a manuscript of various medieval documents relating to the diocese, provides valuable information for that period. In 1201 an enquiry was held into the ecclesiastical property of the diocese. The jury who conducted this survey was made up equally of Irish, Norman and Viking members indicating the cosmopolitan nature of the diocese at that time. This invaluable list of early thirteenth century churches is printed and discussed in Begley’s History of the Diocese. In the taxation return for 1302 we learn for the first time that the diocese had been divided into deaneries and the proxy tax of 1418 gives another list of churches which affords a valuable comparison with the situation in 1201. It is to Cornelius O’Dea, bishop from 1400 to 1426, that we are indebted for the two great treasures of the diocese, the O’Dea mitre and crozier. He was also responsible for the compilation of the Black Book, which was returned to its rightful home in the diocese during the recent episcopate of the late Bishop Newman.

Changes after the Reformation

At the Reformation, Bishop John Quin, a Dominican of Kilmallock friary accepted the limited changes of King Henry VIII, as his successor Bishop William Casey did the Lutheran system of Edward VI. Following the restoration of papal links under Queen Mary, Casey was dismissed and Hugh Lacy, a member of the prominent Co. Limerick Anglo-Norman family was appointed bishop. He remained in office until 1571, when he was removed by Queen Elizabeth and William Casey was restored as bishop. It is from this date that the final cleavage occurred and henceforth there were to be separate bishops for the catholic and anglican dioceses. Bishop Lacy died in 1580 and two years later the Holy See appointed Cornelius O’Boyle as bishop. He was then in Spain, where he appeared to have remained until his death in 1597.

The history of the 1600's

Limerick was without a bishop for a further twenty years until Richard Arthur, who had been vicar general, was appointed. On his death in 1646, he was buried in St. Mary’s Cathedral which had come into catholic hands during the Confederate wars of the 1640’s. His successor, Dr. Edmund O’Dwyer, undertook a re-organisation of the diocese and his report to Rome in 1646 gives a valuable insight into the situation of the diocese at that time. He survived the charge of the city by Ireton in 1650 and after the surrender escaped to Brussels, where he died in1654. The difficult Cromwellian period was followed by a more tolerant approach after the restoration of Charles II. In 1677 a new bishop, Dr. James Dowley was appointed. Two years later he sent an optimistic report to Rome on the state of the diocese. Education was flourishing, with schools in every parish and a weekly sermon on Sundays. He established two confraternities and visited each parish in the diocese, regularly ordaining priests. Even during the brief persecution occasioned by the Popish Plot, he was not hindered in his episcopate and lived until 1685, which year saw the catholic monarch James II ascend the throne. Dr. James O’Moloney was transferred from the see of Killaloe to Limerick in 1689. However, he left for the continent before the 1690 siege, leaving the administration of the diocese in the hands of his cousin, Dr. Matthew Moloney and Dr. James Stritch; vicars general during the tumultuous period of the sieges and subsequent treaty of 1691.

Limerick was without a bishop for a further twenty years until Richard Arthur, who had been vicar general, was appointed. On his death in 1646, he was buried in St. Mary’s Cathedral which had come into catholic hands during the Confederate wars of the 1640’s. His successor, Dr. Edmund O’Dwyer, undertook a re-organisation of the diocese and his report to Rome in 1646 gives a valuable insight into the situation of the diocese at that time. He survived the charge of the city by Ireton in 1650 and after the surrender escaped to Brussels, where he died in1654. The difficult Cromwellian period was followed by a more tolerant approach after the restoration of Charles II. In 1677 a new bishop, Dr. James Dowley was appointed. Two years later he sent an optimistic report to Rome on the state of the diocese. Education was flourishing, with schools in every parish and a weekly sermon on Sundays. He established two confraternities and visited each parish in the diocese, regularly ordaining priests. Even during the brief persecution occasioned by the Popish Plot, he was not hindered in his episcopate and lived until 1685, which year saw the catholic monarch James II ascend the throne. Dr. James O’Moloney was transferred from the see of Killaloe to Limerick in 1689. However, he left for the continent before the 1690 siege, leaving the administration of the diocese in the hands of his cousin, Dr. Matthew Moloney and Dr. James Stritch; vicars general during the tumultuous period of the sieges and subsequent treaty of 1691.

From the 1700's to today

The diocese was again without a bishop during the early years of the eighteenth century when much anti-catholic legislation was passed by the Irish parliament. A new bishop, Dr. Cornelius O’Keeffe, was eventually appointed in 1720 and managed to administer the diocese successfully despite the legal restrictions. In the 1780’s, during the episcopate of Dr. Conway, a report to Rome on the state of the diocese demonstrates that the church did not suffer as severely under penal legislation as is often supposed. The diocese was divided into four decanates each presided over by a vicar forane who held a conference of its priests once a month. The forty parishes of the diocese each had a chapel with at least basic facilities and there was no shortage of priests. The mass rocks of popular folklore were clearly not the normal location for the mass. The chapels in the five city parishes were larger and more ornate. There were no convents of nuns and the report notes with concern, the refusal of some clerical students to return to the diocese after ordination at the continental colleges. In 1825, Dr. John Ryan from Tipperary, was appointed coadjutor bishop with right of succession to the elderly and infirm Charles Tuohy. The grant of Catholic Emancipation in 1829 revitalised the church in the diocese and during the long episcopate of Bishop Ryan and those of his successors, Bishops Butler and O’Dwyer, there were major programmes of church building, parish reorganisation, liturgical innovation and spiritual renewal. Their record of achievement and commitment to the diocese has been continued and expanded by their twentieth century successors: in our own time, by Bishops Murphy, Newman and Murray – in the see established by Gilbert nine centuries ago.

The diocese was again without a bishop during the early years of the eighteenth century when much anti-catholic legislation was passed by the Irish parliament. A new bishop, Dr. Cornelius O’Keeffe, was eventually appointed in 1720 and managed to administer the diocese successfully despite the legal restrictions. In the 1780’s, during the episcopate of Dr. Conway, a report to Rome on the state of the diocese demonstrates that the church did not suffer as severely under penal legislation as is often supposed. The diocese was divided into four decanates each presided over by a vicar forane who held a conference of its priests once a month. The forty parishes of the diocese each had a chapel with at least basic facilities and there was no shortage of priests. The mass rocks of popular folklore were clearly not the normal location for the mass. The chapels in the five city parishes were larger and more ornate. There were no convents of nuns and the report notes with concern, the refusal of some clerical students to return to the diocese after ordination at the continental colleges. In 1825, Dr. John Ryan from Tipperary, was appointed coadjutor bishop with right of succession to the elderly and infirm Charles Tuohy. The grant of Catholic Emancipation in 1829 revitalised the church in the diocese and during the long episcopate of Bishop Ryan and those of his successors, Bishops Butler and O’Dwyer, there were major programmes of church building, parish reorganisation, liturgical innovation and spiritual renewal. Their record of achievement and commitment to the diocese has been continued and expanded by their twentieth century successors: in our own time, by Bishops Murphy, Newman and Murray – in the see established by Gilbert nine centuries ago.

The diocesan logo explained

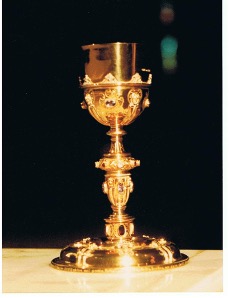

Symbols: the chalice and host

The chalice and eucharistic host are used as they are immediately evident sacred icons which represent elements of the eucharist. The chalice also has strong associations with the Limerick region and in particular Ardagh. The abstract heart shape is a more modern version of the traditional symbol which represents love, fidelity and constancy.

The hands:

Traditionally the hand is used in religious art to symbolise prayer. One of the mosaics in the chapel of the Irish College, Rome, depicts the hands of Our Lady in the traditional orans position, used in icons to denote prayer. In addition, hands illustrate the following qualities to which the Diocese of Limerick aspires;

- Community spirit

- Friendship

- Support

- Togetherness

- Unity

The window:

The classical Romanesque style window - readily recognisable for its religious associations - was chosen to frame the symbols of the new logo. At once, the window adds a unity and clarity to the diocesan logo.

The colours:

Green, the primary background colour used, was chosen to represent Limerick.

Green also represents nature and balance.

Complimentary colours are introduced to the design to represent the many communities and cultures included in the Diocese of Limerick.

The blue of the chalice represents a calm and peaceful support.

The use of three very distinct colours echoes the Holy Trinity representing the catholic faith of the diocese.